KARACHI: Amid the forty-degree heat that paralyzed the coastal city of Karachi in April, Saad Saleem blasted his air-conditioning with near-abandon.

Electricity tariffs have surged, but the affluent entrepreneur has been unbothered since he spent $7,500 installing solar panels on his bungalow’s roof as part of a solar boom in Pakistan.

Saleem bought his modules two years ago, as the International Monetary Fund and economically beleaguered Pakistan were hammering out a preliminary bailout program. Under the deal, Pakistan sharply raised power and gas tariffs to support struggling suppliers in the heavily indebted sector.

Pakistanis now pay more than a quarter more on average for electricity, setting off a scramble to install solar modules.

Solar made up over 14 percent of Pakistan’s power supply last year, up from 4 percent in 2021 and displacing coal as the third-largest energy source, according to UK energy think-tank Ember. That is nearly double the share in China, the world’s top supplier of solar panels and a global leader in green technologies, and one of the highest rates in Asia, according to Reuters’ analysis of Ember data.

But the explosion in solar uptake has left out many in Pakistan’s struggling urban middle class, who have been forced to cut back on electricity in face of soaring bills, according to interviews with more than two dozen people, including energy officials, consumers and power-sector analysts. Most of the nation’s solar panels aren’t connected to sell excess capacity to the grid, so the benefits of cheap and reliable power aren’t widely shared.The flight of affluent Pakistanis with solar access from the national grid has dealt a further blow to those relying on pricey conventional sources of power. Electricity companies that lost their most lucrative clients have been forced to additionally hike prices on their shrinking pool of customers to cover operating costs, according to Arzachel, a Karachi-based energy consultancy.

Syed Fahim Ali, 30, uses a wiper to clean the solar panels installed on the roof top of his home, in Karachi, Pakistan April 5, 2025. (Reuters)

Some observers also blame financial stress in the energy sector on deals Pakistan made with China for Beijing to finance billions of dollars’ worth of power-generation contracts, many of which involve coal-fired plants. Pakistan is behind on many of the payments and has been in talks with China about extending the time it has to repay the debt.

Countries like South Africa also face widening energy gaps after affluent residents adopted solar power. But analysts are watching Pakistan particularly closely due to the pace at which the nation of 250 million has taken to sun-based energy.

“This could serve as a cautionary tale as to how regulation and policy needs to keep up with technological change and rapidly evolving economics,” said Haneea Isaad, an Islamabad-based energy finance specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

In an interview with Reuters, Pakistan power minister Awais Leghari acknowledged the energy gap but noted that tariffs have come down significantly since June 2024, when the IMF approved reductions.

He also pointed to heavy uptake of solar by rural Pakistanis, many of whom previously had limited access to the grid. Many non-urban Pakistanis have installed small solar setups to meet their power needs, which are typically far lower than those of their city-dwelling counterparts.

“Pakistan has actually gone through a solar revolution,” he said. “The grid is going to get cleaner by the day, and this is something that we’ve achieved as a nation that we are proud of.”

The IMF did not return requests for comment.

ENERGY DIVIDE

Just a few miles away from Saleem’s upscale neighborhood, Nadia Khan has restructured her life to cut electricity costs.

The air-conditioning in the homemaker’s apartment is rarely used and she’s stopped ironing most of the clothes worn by her family of five, citing the price of power.

Khan’s family is not alone in cutting back: Only 1 percent of paying consumers used over 400 units of power in 2024, per Karachi-based consultancy Renewables First, down from 10 percent before the pandemic.

Like others among Pakistan’s masses of apartment dwellers without space to install solar modules, Khan has been shut out of the revolution.

The roofs of many apartment buildings are designated for water storage and other sanitation purposes, while owners of rental buildings have little incentive to invest in solar connections for their tenants.

“We get some sunlight indoors but I can’t seem to think of a way to go solar,” she said. “Why must people living in apartments suffer?“

Meanwhile, land-owning Pakistanis have benefited from the glut of Chinese-made low-cost solar modules shut out of the West by high tariffs.

A worker unloads solar panels from a vehicle at a market, in Karachi, Pakistan March 26, 2025. (Reuters)

China exported 16.6 gigawatts of solar capacity to Pakistan last year, according to Ember, about five times as much as in 2022. The average cost per watt of solar-module capacity exported also fell 54 percent in the same period.

However, most solar setups aren’t configured to send spare power back to the grid, limiting their benefit to the wider public. Renewables expert Syed Faizan Ali Shah, who advises the government on solar adoption, has said that less than 10 percent of solar consumers sell excess power to the grid.

Experts and government officials blame high costs and sanctioning delays. Connecting a solar module to the grid usually takes between three and nine months, said Renewables First energy expert Ahtasam Ahmad, prompting many to not bother.

Converting power generated from a solar panel for transmission to the grid also requires equipment like inverters, which typically cost between $1,400 and $1,800, or roughly half the median household income in Pakistan.

SUNK COSTS

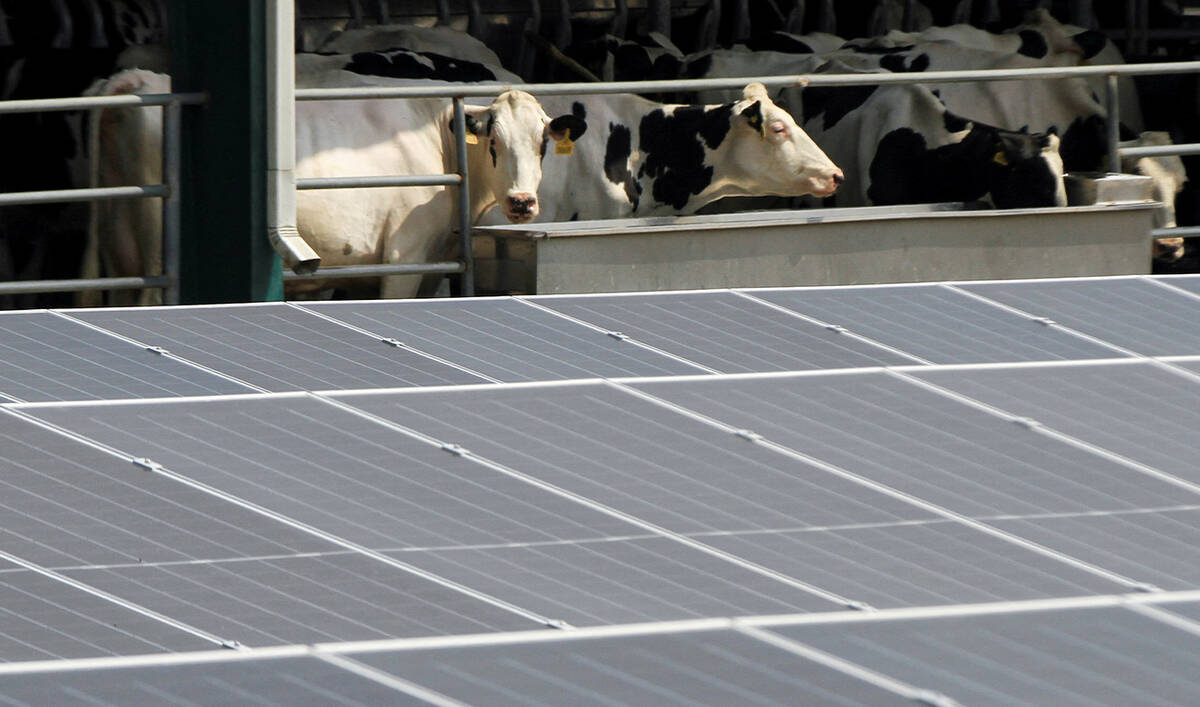

Pakistan conglomerate Interloop has installed hundreds of solar modules next to its cowsheds in Punjab province that help provide the electricity keeping its 9,300 livestock cool and their milk chilled.

The investment in solar has been a lucrative one for Interloop, which typically breaks even on solar installation costs after three to four years. Basic operating costs are about three quarters less than payments to the grid, said Interloop energy manager Faizan Ul Haq.

The money Interloop saves also reflects a gaping hole in the accounts of Pakistan’s power companies.

View of solar panels with cows in the background at an Interloop owned dairy farm, in Sheikhupura, Pakistan April 8, 2025. (Reuters)

Even though industrial groups and wealthier Pakistanis now consume less grid power, suppliers’ costs haven’t changed proportionately. Fixed expenses like fuel contracts and upgrades to transmission architecture accounted for about 70 percent of supplier expenditure in the year to June 2024, according to an Arzachel estimate.

To cover costs, suppliers have raised prices on their remaining customers, who have already faced repeated increases as a result of the IMF deal.

Fixed costs of 200 billion rupees were shifted to non-solar consumers in the 2023-2024 fiscal year, meaning they paid 6.3 percent more per kilowatt-hour than they otherwise would have, according to Arzachel data.

Solar panel imports have increased since, meaning grid demand is likely to continue dropping, forcing remaining customers to pay more.

“Pakistan’s experience demonstrates a crucial lesson: when governments fail to adapt quickly enough, people take charge,” said Ahmad of Renewables First.